The Gossner Evangelical Lutheran church is active in Jharkhand since 1845, that is an impressive 172 years now (2017).

That the Lutherans would be the first Christian missionaries in Jharkhand, and that they showed up in Jharkhand at all, to a large extent were accidents of history. People plan, but plans can be fruitless or take unexpected turns.

The first plans implied the HOS of Singhbhum. In 1840, J. R. Ouseley took over from Thomas Wilkinson as Agent to the Governor General on the South Western frontier, what now is approximately Jharkhand. He soon went to inspect the recently (1837) instituted Kolhan Government Estate, that is, by and large, the Hodisum. Here, he found that the HOS did not have castes, did follow none of the major religions and, important for him, would eat ‘from the British table’. Moreover, they had a good opinion of the British – at least that’s what they told him. They were, therefore ‘a bolder and finer race than most of the people of the country’.

Ouseley thought that this was too good a chance to let pass. He asked the Bishop of Calcutta to send Anglican missionaries to Singhbhum because, as he wrote, ‘a finer field for the Missionary never existed’. He pressed his point that the conversion of the HOS was ‘of the highest importance, far exceeding what could be done even with the expenses so cheerfully afforded to convert the population of some small and distant island in the Pacific Ocean’. Indeed, the Christianisation of the Hos and we may presume other tribals, could be the start of ‘the general conversion of India’. But Ouseley received no reply. He had overstepped his brief. Anglicanism was tied to officialdom and Calcutta prescribed a cautious line of non-interference with Indian beliefs and practices, with the exception of extreme practices like infanticide and widow burning (sati). Christian conversion was not on its agenda. But the East India Company could not well deny missionary activity to non-British in India.

Still, it was only by chance that the first four missionaries, the Germans Emile Schatz, August Brandt, Friedrich Batsch and Theodore Janke, arrived in Ranchi. They were on their way to the Karens in Burma, but found on arrival in Calcutta that the American Baptist missionaries were already working there. So much for communications in those days. Then they made the plan to go to the Shimla area as they thought that this town was on the way to Tibet, but the First Anglo-Sikh war (1845-1846) made that route impossible. So, they were stuck in Calcutta.

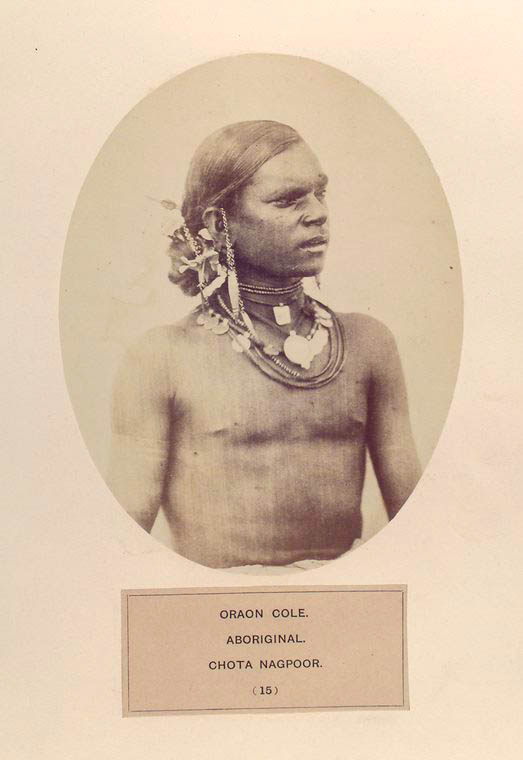

On a walk in Calcutta, the Germans saw some “natives with a dark skin” cleaning drains and doing other heavy work. Labour migration of these people to Calcutta was already noticed in 1820 by Roughsedge, and in 1832 by nobody less than Charles Metcalfe. In his famous Minute on the causes of the Kol Insurrection of 1831-1832, he wrote that the town was “swarming” with tribals from Chotanagpur. But that is another story.

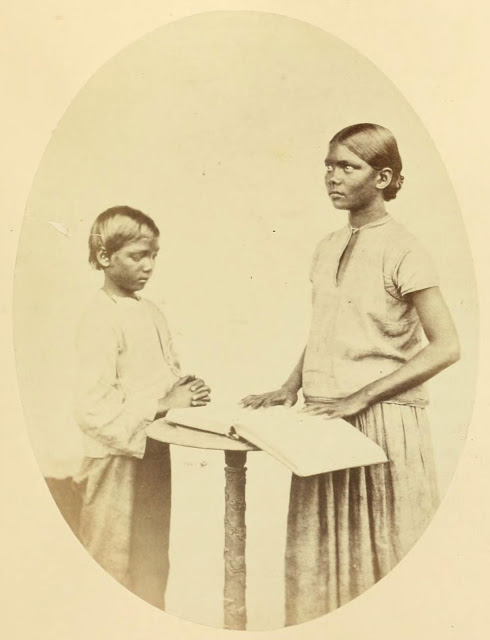

Their host Mrs Hoeberling told them, that these were “Dhangars”, another name for Oraons. She had heard that the recently demised Reverend De Rodt, a Swiss missionary who was well versed in Bengali, had approached these people and that they had told him they had come from Chotanagpur. That gave the four missionaries the idea they might as well go into that direction. While they were staying at Bankura, Dr Hoeberlin, the husband of Mrs Hoeberling, went on to Chotanagpur and brought back an invitation from the Agent J. R. Ouseley and his Assistant Hannington. That last one was seen as the driving force behind the decision to allow the missionaries, but it is hard to escape the notion that Ouseley saw a chance here to implement his earlier plan. The four arrived in Ranchi on 2 October 1845, and after a few days in tents, settled on the spot of the present-day Lutheran church. It took them five years, till June 1850, to get the first conversions, four Oraons. The church was built in (again) four years with money from Germany, and finally consecrated on Christmas 1855.

At the start of the Mutiny in 1857 the number of converts was still low, about 700, served by some twelve German missionaries. But, maybe, because they had some backing by the Church or, certainly, because they were more educated, Christians were vocal in defending their rights. There had been at least one major clash in 1855.

In 1857, just before the Mutiny reached Jharkhand, the rumour – also in those days rumours were rife – had it that the German missionaries had offered 10,000 Christians and their friends as support for the troops loyal to the British. Wisely, this spurious offer was turned down by the officers. When things got serious, Dalton could recruit a mere 25 Christians to his forces.

The Mutiny broke out on 30 July 1857 in Hazaribagh. The mutineers soon set off to Ranchi where they arrived on the 2nd of August. Their main targets were the treasury, the ordinance (one never has enough munition), and the bungalows of the East India Company officials. The plunder took place in all quiet, and though many documents were destroyed, there cannot have been much property to carry away. The Mutineers fired their cannon at the church building. Firing cannon balls on a church served no military purpose; it could well have been out of frustration. One of these cannonballs still is visible in the tower.

The missionaries had fled, as many Europeans had, to Calcutta, and the local Christians as far as they were in Ranchi, went back to their villages. There, they got a rough deal from the landlords. The village of Prabhusahay was “levelled to the ground”, another was “burned to the ground”. Possibly, the scale of destruction was overdone in the sources, because about one village, Hethakota, we hear only about a single house that was ransacked. Rather symbolically, the local landlord of Hatia set a price of on the head of Rvd Schatz, three named Christian villagers, and any British officer.

Possibly it the landlord of Hatia who taunted the Christians to open their book, and to “Sing to us now one of you sweet songs.” Here the missionary chroniclers (many of these wrote years after the events when by repetition and time the stories had got set patterns), clearly got carried away by their Bible, more precisely a psalm (172) describing the Jewish Captivity: “By the rivers of Babylon we sat and wept when we remembered Zion. … For there our captors … said, “Sing us one of the songs of Zion!”

It is easy to overstate the role the missionaries during the Mutiny. They were “people of the book”, and hence rather prolific writers who left quite a paper trail. But it seems that at best they were a symbolic target for the Mutineers. And, likewise, at best a token support to the British.

Within two months, by the end of September, beginning of October the main hostilities in Chotanagpur were over. The missionaries came back. But Pastor Schatz left for Germany.

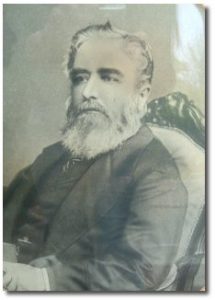

After the Mutiny the number of Christians got up. Not that the colonial administration liked that too much, at least in the beginning. In 1859, in the unsettled times right after the Mutiny, Commissioner Edward Tuite Dalton called the Lutherans “a new band of agitators”. However, relations between the Commissioner and these early missionaries eased soon, and when in 1868 the Lutheran church split, Dalton supported them with 7,000 followers to come over to the Anglican denomination. The bulk of the Christians, some 15,400, remained with the Lutherans. The church building and schools remained in Lutheran hands to this day.

Dalton was ambivalent about the strict Christianity introduced in Chotanagpur. In 1868, he wrote that the missionaries, apparently both Lutherans and Anglicans, had gone much too far, with prohibitions of dancing, taking diang/hanria, and even of wearing ornaments.

Of course, as in all such situations, people did these on the sly and as far as I know, present-day Christianity in Jharkhand has done away with this strictness.

A shorter version was published on Facebook, 29 October 2017