A THOUSAND YEARS OF LOVE

Book review of E. Powys Mathers, Black Marigolds, Oxford: B.H. Maxwell, 1919

I was curious for Bilhana’s poems ever since I read some in John Steinbeck’s Cannery Row in the leasure filled days leading just before my graduation. From time to time, I thought about them, softly and in passing, as if remembering a meeting with a warm and beautiful lady who had drifted out of my life too soon.

Recently, however, while working on my collection of old prints of tribal history and poetry, I was surprised to find that nobody less than William George Archer mentioned Edward Powys Mathers. My HO friends know Archer as the editor of the “Ho Durang”, HO Songs, the first book ever (1942) printed in the HO language. He mentioned Powys Mathers in an essay on translation of poetry in his friend Verrier Elwin’s “Folk-songs of Chhattisgarh”, in 1946.

Here is the connection. One year earlier, 1945, John Steinbeck had published “Cannery Row”, a novel about a small establishment on the coast of California, where people lived in a mixture of deep poverty and bohemianism. Its intellectual and cultural centre was Doc who made his living by selling rare sea animals to labs all over the land. Doc was Steinbeck’s close friend Ed Ricketts – and Cannery Row is a real place.

The high point of the book is a surprise birthday party at Doc’s place. At the end, when everybody, even the boys and girls from next door, was tired and quiet, Doc read a couple of poems from the Sanskrit. He started:

Even now

If I see in my soul the citron-breasted fair one

Still gold-tinted, her face like our night stars,

Drawing unto her; her body beaten about with flame,

Wounded by the flaring spear of love,

My first of all by reason of her fresh years,

Then is my heart buried alive in snow.

And as the party listened, “A little world sadness had slipped all over them. Everyone was remembering a lost love, everyone a call.”

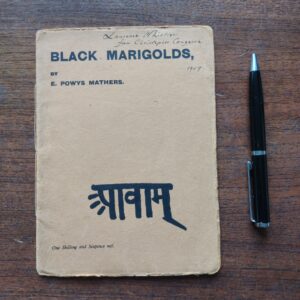

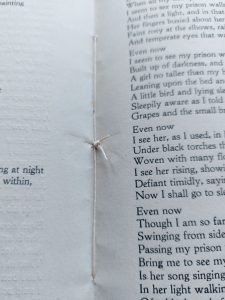

The Brit Edward Powys Mathers had made the translation. It was published in 1919 as ‘Black Marigolds’. At the time, Indian poetry was virtually unknown outside of India; and it was a minor sensation. Once I saw the booklet on an antiquarian’s website for a crazy amount as it was advertised as “indispensable for the John Steinbeck specialist”. But I remembered it for the poems. I found it again on a website for some price which, after some quite irresponsible reasoning with myself, I could afford. Now it had arrived in my house.

I had never thought of its appearance. It turned out to be a small booklet, 19 to 14 cms., not unlike the semi-official and very critical magazine we stencilled in our students’ days. It could have fitted in an envelope, but it was packaged like a book. The cover was of soft, a bit oily, thick paper. Its 22 pages were not all of the same size. They were held together by a hand knotted cord. An old, rustic way of publishing poetry. Occasionally, we still call a poetry collection a sheaf of verse. Well over 100 years old, it felt fragile. To keep it in one piece, it needed a protective cover. I rushed to the shop, and everybody I encountered on my way greeted me with a huge smile.

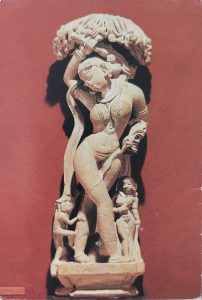

The collection is known as the Caurapañcāśikā, the fifty poems of Chauras. Or, more informative but certainly less flattering, The Love Thief. Edward Powys Mathers called the poet Chauras, but by now he is more widely known as Bilhana. He was a young poet, who fell in in love with his pupil. But she was the younger daughter of the king. As fathers do on discovering a secret affair of their daughter, he directed his anger towards the boy. And as kings do, he condemned the astray teacher to death. In the last night in his cell, the young lover composed fifty completely unrepentent poems. They capture that mood of being so enraptured, that even death loses its importance. It is expressed at the start of each poem in the repetitive Adyapi, here rendered as “even now”.

Even now

I remember that you made answer very softly,

We being one soul, your hand on my hair,

The burning memory rounding your near lips;

I have seen the priestesses of Rati make love at moon-fall

And then in a carpeted hall with a bright gold lamp

Lie down carelessly anywhere to sleep.

The poems have lost nothing of their impact. Hardly any glossary was needed. Glossaries are, I found, especially loved by academics who have reached the outer limits of their command of language. I knew a Sanskritist who spent 15 years translating an 85 lines short poem on flowers and insisted on tracing their scientific names. He was always drunk whenever I spoke to him. He died early.

Edward Powys Mathers ( 1892-1939) was better at it. But, at least in the eyes of my deceased friend, he was cutting corners. Mathers did not mention which manuscript he used, but from his preface we can guess that he used Edwin’s Arnold’s 1896 “An Indian Love-lament”, in both Sanskrit and English. It could also have been Arnold’s source, a translation made in 1833 by Peter von Bohlen, a pioneer of Sanskrit studies in Germany. Von Bohlen’s was in Latin , and Arnold’s translation was quite loose. So Powys Mathers had to start again from the Sanskrit text itself. He wrote defensively that although some verses were indeed direct translations, other should be considered “an interpretation rather than as a translation”. It was this modesty, or realism, that had attracted William Archer. But Mathers had been on fire. He translated the fifty poems in 1915 when he was 23 years old, in “two or three sessions, sitting on a box by the stove in hutments”, not daring to disrupt the flow by moving to “more luxurious minutes and places”. He succeeded admirably. The mood and the imagines speak directly to us about the rush of being in love.

Even now

I seem to see my prison walls come close,

Built up of darkness, and against that darkness

A girl no taller than my breast and very tired,

Leaning upon the bed and smiling, feeding

A little bird and lying slender as ash-trees,

Sleepily aware as I told of the green

Grapes and the small bright-coloured river flowers.

####

How did it end for the people involved in the poetry reading in Cannery Row?

Edward Powys Mathers went on to make an over 2,000 pages long translation from a French version the “Thousand and One Nights”; then continued as a a composer of cryptic crosswords for The Observer. He died in his sleep in 1939. He was 46 years old.

Doc, the marine biologist and philosopher Ed Ricketts, died in 1968 at the age of 50, when his car was hit by a train.

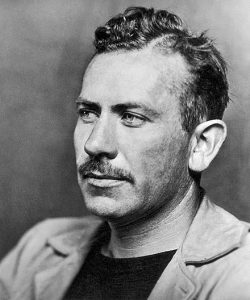

John Steinbeck continued as an author, and received the 1962 Nobel price for literature. He died, 66 years old, in 1968, of a heart failure. He had been a heavy smoker.

And our poet and his lover? The sources are not unanimous. Mathers gives Chauras’ poems as composed in the last few hours of his life. But then again, that could well be an embellishment of history, as poems have to be polished after the first rush of writing. Luckily, there also is a south Indian collection (See Ed Ariel below) with a happier ending. Chauras was merely exiled. Some say, he even married his princess, but contrary to the opinion of the poet, she is always treated as a minor character. Indication is that each source gives her another name. Our poet himself ended up at the Chalukya court, composing the Vikramankadeva Caritam, the history of Vikramaditya VI. In it, he reveals himself as Bilhana, hailing from Kashmir. Some say that was in 1080, others in 1120. Forty years difference! That’s a huge gap for a historian.

Important? In the end, maybe not. The verses of the love thief were written long before Bilhana finally disclosed his name. It is said that poetry transcends times and places. From nearly 1000 years ago in a dark cell in India, to a bit over 100 years ago on a box in a hutment in England and on to a reading 80 years ago in a store room of preserved fishes on the coast of Calfornia. Scholarship can be frightfully exact, but it cannot compete with the beats of the poet’s heart.

Even now

I know that I have savoured the hot taste of life

Lifting green cups and gold at the great feast.

Just for a small and a forgotten time

I have had full in my eyes from off my girl

The whitest pouring of eternal light.

The heavy knife. As to a gala day.

= = = = = = =

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Archer, William George. “Comment” in Elwin, Verrier, Folk Songs Of Chhattisgarh, 1946, Oxford University Press, pp. xi-xxxviii, https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.238331/page/n11/mode/2up

Ariel, Ed. (traduit et commenté). “Tchorapachacat”, in Journal Asiatique ou recueil de memoires (cinquieme serie tome.XI), 1848: pp. 469-334. https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.26144/page/469/mode/2u

(First Sanskrit text (pp. 469-489, then French translation (pp. 490-505). “donne un préambule étendu destine á expliquer l’occasion de ses amours.”. The translation of the fifty poems starts on p. 498. Happy ending, the king gives his daughter on p. 505. Notes, Variantes, metres employés, coomentaire, Observations de detail. par Ed Ariel, Pondichery, 8 Octobre 1947. )

Arnold, Edwin. The Chaurapanchâsika: An Indian Love-lament by Bilhana, 1896, K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & co., ltd. https://archive.org/details/chaurapanchsika00bilhgoog/page/n6/mode/2up

Bohlen, Petrus a. Bhartriharis sententiae et carmen quod Chauri nomine circumfertur eroticum, Berolini, Impensis Ferdinandi Duemmleri, 1833, https://books.google.nl/books?id=YhIpAAAAYAAJ&printsec=frontcover&hl=nl&source=gbs_ge_summary_

Datta, Bagala Kant, हो दुरंग (Ho Durang), A HO Songbook, , with preface by W.G. Archer, Patna: Yunāiṭeḍa Press Ltd.1942.

Journal Asiatique ou recueil de memoires (cinquieme serie tome.XI) 1848: p. 70 https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.26144/page/69/mode/2up Avec préambule. Sur papier Européenne.

Misra, B.N. “Caurapancásiká” in Studies on Bilhana and his Vikramankadevacarita, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi: K B Publications. 1976, pp 115-125. https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.65721/page/n125/mode/2up (A useful bibliography on different versions of the The Caurapancâsiká.)

Nurse, Julia. Lovesickness and ‘The Love Thief’, 14 February 2018. https://wellcomecollection.org/articles/WoMM-yoAACoANz7M (on Edwin Arnold 1896 version and some 20th century literature leads).

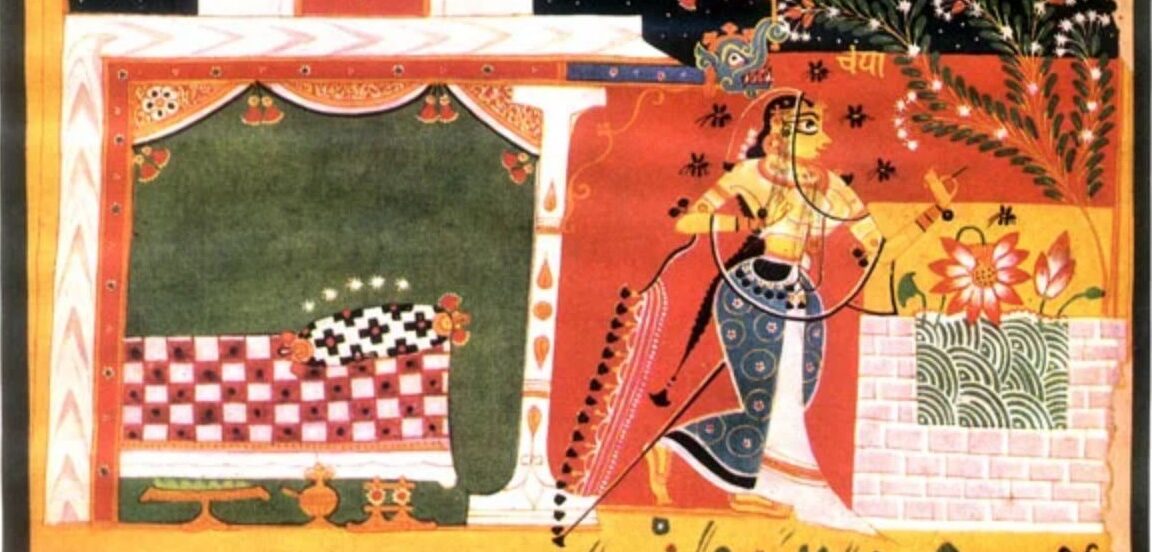

Shiveshwarker, Leela. Chaurapañchāsíkā : a Sanskrit Love Lyric; Publications Division, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India, 1994. https://archive.org/details/chaurapanchasika00shiv/page/n3/mode/2up (An illustrated edition)

Steinbeck, John. “Cannery Row” in: Of Mice and Men, Cannery Row. Penguin Modern Classics, 1973, pp. 103-270. (Cannery Row 1st published 1945)

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. “Editions and versions” and “Translations” in Caurapañcāśikā, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caurapa%C3%B1c%C4%81%C5%9Bik%C4%81